The protagonists of the text are the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch, his paint brushes, the software developer Adobe and bird poo.

Painter by the Wall

Painter by the wall is one of the last paintings of Edward Munch. It was painted in 1942

just two years before his death.

The painting shows an outdoor scene of a painter standing on a ladder painting the wall of a

house. The house is Munch's villa in Ekely, his last residence. It is spring, the garden is lush

and green, the bushes are blooming in a bright yellow.

Munch is mostly known for his symbolically and emotionally charged paintings from the 1880s and

1890s like The Sick Child or The Scream. They're often read as existential

struggles with the world. But unlike this earlier period, there is no anxiety or pain to be

found in this painting.

Painter by the wall is part of Munch's later stage of work that began after several

breakdowns and hospitalization in the years of 1908 and 1909. In the 1930s and 1940s he produced

a number of paintings that seem like observations of everyday life, mostly outside, most of them

manual labor: A farmer plowing a field, another making hay, someone picking apples and here a

painter painting a wall.

Painter by the Wall, 1942, oil on linen, Munch Museum Oslo

Painter by the Wall, 1942, oil on linen, Munch Museum Oslo

What we're witnessing here is Munch painting someone in the act of painting. When he himself was

painting Painter by the Wall, he had been an artist for more than 60 years. Was he

thinking about whether the painter in his painting might not only be the ordinary house painter

but a reflection on his own profession?

I was trying to look at the painting to see if there is a hint to determine which kind of

painter we're dealing with here.

I open up the reproduction of the painting on my computer and try to take a closer look at this

painter. Is there anything in his gestures, in the way he holds the paint brush that gives an

answer?

What kind of hand and brush are they, the one of the laborer or the one of the artist?

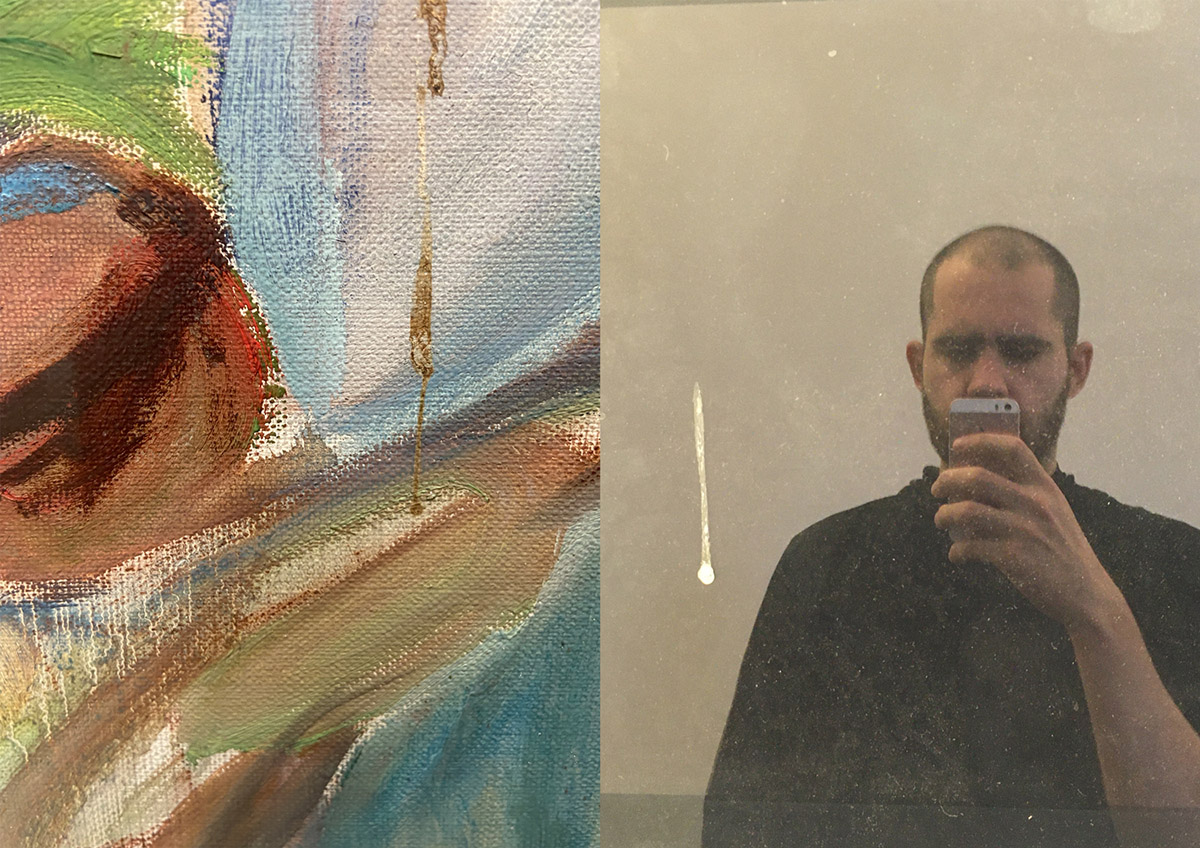

I zoom in and look at the painter's arm that reaches out towards the house in front of him. His

hand and brush are kind of mashed together into one red brownish brushstroke. It's not quite

clear what his brush touches. It's pointing towards the space between the wall, window bar or

even the glass of the window.

If he were to paint the wall, that would make him the ordinary house painter, whom Munch

probably observed on some spring day in 1942. The gestures of this painter are not filled with

any deeper meaning other than spreading the paint evenly over the surface of the wall.

But could he instead be painting the glass of the window?

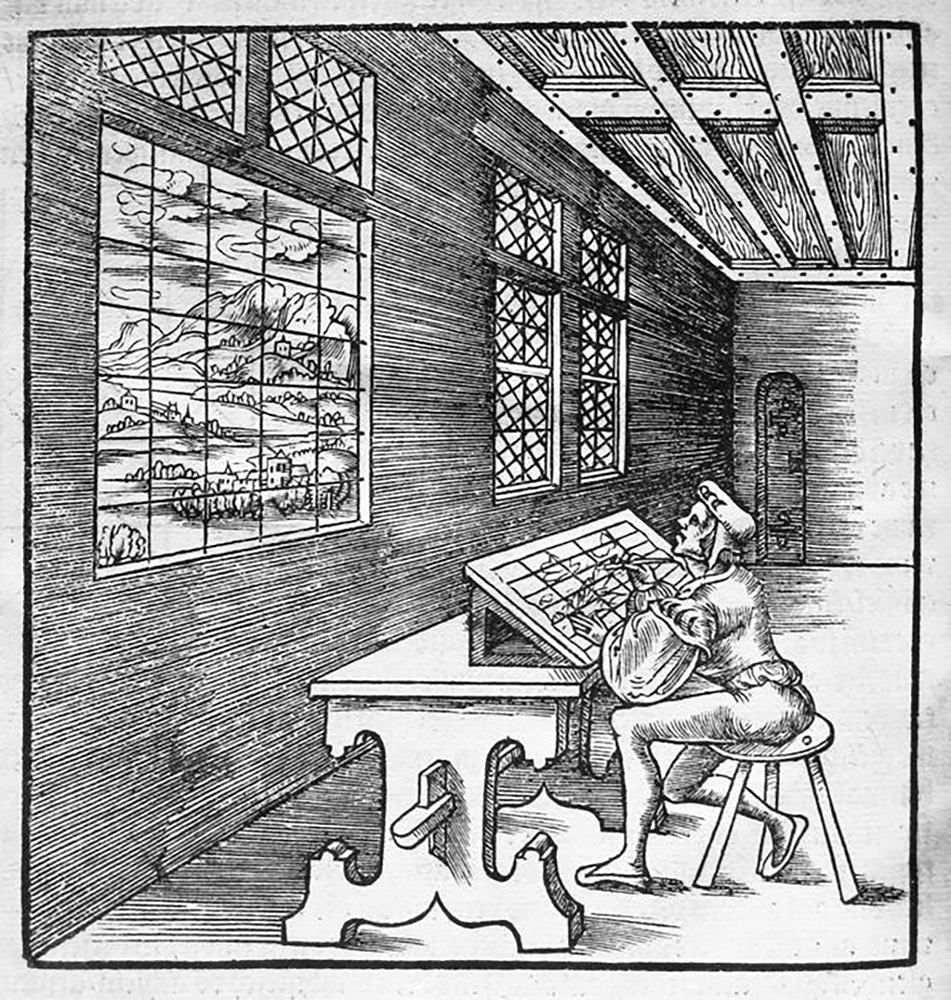

In western art history the metaphor of painting as an act which produces windows can be traced

back to the 15th century. In one of the first accounts of this Leon Battista Alberti describes

in De pictura how the two-dimensional plane of a painting is transformed into a

representation of a three-dimensional space. The surface gives way to whatever appears behind

the window that the painting has become.

This would mean that Munch's Painter is not a painter who just paints walls but an artist like

Munch. One who paints surfaces on canvas that act like windows to other spaces.

Woodcut Illustration of Alberti's window by Hieronymus Rodler

Woodcut Illustration of Alberti's window by Hieronymus Rodler

Walls and Windows

One of the functions of a window is to let the view pass through itself. The more the

window shows what's behind it the better it's working and it works best the moment the window

itself becomes invisible.

Right now the computer screen in front of me is also acting like a window to Munch's painting

How could one describe those parallels between Munch's window and the computer screen that are

superimposed right now in front of me?

I will try to approach the question through the interface, a figure of thought that will

recur throughout the text.

In its most basic understanding an interface is a “significant surface

This definition emphasizes the window or picture-like aspect of the interface.

However Munch's painter being undecided between wall and window hints that the story of the

interface is not only told by the window.

As in Munch's painting, where there is a window there is a wall.

And like the decision that Munch's Painter is facing between wall and window, this is something

that the interface is also always in between. Between the surface and the meaning

delivered through it.

The longer I look at the painting it seems as if the Painter is actually painting the

window-frame.

The frame is located where the wall and window meet. It's the edge of the window.

And if Alexander Galloway says in relation to interfaces: 'the edges of art always make

reference to the medium itself.'

A 3-d print leaning against the window of my studio

A squirrel peeking through the window into my studio

In François Dagognet writing on interfaces he describes the interface as “an area of choice.

It both separates and mixes the two worlds that meet together there, that run into it. It

becomes a fertile nexus.'

This fertile nexus is located between inside and outside of an interface, between frame

and glass, between wall and window, between surface and meaning delivered through

it.

Where is this fertile nexus in Munch's painting? If we see the painting not only as a window to

the scene in the garden but as an interface that consists of a painted surface we can see it

moving back and forth between the depicted scene and the brushstrokes it is made of.

I can look at the window in the painting and see the dark green spots as reflections of the

garden in the window glass. Or I could see them as a surface and patches of paint.

And I can look at the paintbrush of the Painter, how it's both a paint brush and a

brushstroke at the same time. Speaking with Dagognet, I have the choice to see it as one or the

other. The painting interface separates and mixes the pictorial space and the material of

the painting.

Bird droppings

The building that we see in Painter by the Wall is in Ekely in the outskirts of Oslo. Munch had

bought a property there in 1916 and besides the Villa that was already there he built a few new

studios as well as what has been called his outdoor studios.

These outdoor studios sometimes only consisted of a wall with a tiny roof which protected the

paintings only very rudimentarily from the weather. Munch used these studios for making large

scale paintings as well as sketches for murals.

He would also just leave paintings outside or store them so poorly that a certain percentage of

Munch's paintings from the so called Ekely collection are damaged by rain and wind and wild

animals that roamed around the paintings.

And quite a few of them have bird shit on them from being stored outside. So does Painter by

the Wall, the droppings are right there next to the head of the painter.

Munch's studio in Ekeley today

Munch's studio in Ekeley today

In the summer I leave open the windows of my studio and sometimes a bird flies

through the open window, sits down at some distance and musters me while I'm working at my desk.

Usually after finding some breadcrumbs on the studio floor they leave.

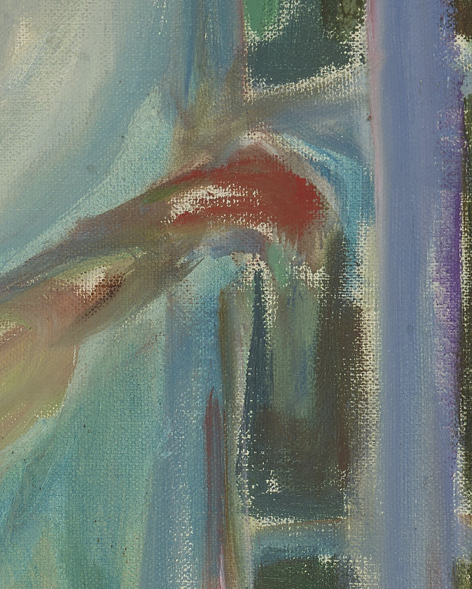

But one morning I entered the studio and when I sat down at my desk I found that one of the

birds had left something on the screen of my computer.

The integrated screen had been broken for a few weeks leaving everything but the screen working.

When I turned it on the screen itself remained a black mirror except for the dried up streak of

bird shit. But it was still humming busily under its mute surface.

When the screen was still working a few weeks ago I had opened up the reproduction of Munch's

Painter By the Wall in Photoshop and looked at the bird droppings on the painting. Now I

wonder whether, for a short moment, the reproduction of the bird shit could have aligned with

the spot on the screen where the other bird shit would find their place.

Maybe they could have aligned for a second, the bird shit formed by the LEDs of the screen and

the real one, both of them only separated by a thin surface of glass.

What was the difference between these two interfaces that both carried bird shit? Clearly, they

were made of different materials, Munch's painting made of canvas and paint and my screen a

glass surface and behind it a complex array of hardware and networks connected to it.

And now, that my screen was broken and wasn't working anymore, now that it wasn't showing

something else on its surface it showed more of itself. I could see it collecting dust

and my reflection in the glass.

But the screen was replaced with a new one and the window pushed back the surface and the

interface started working again.

Where was the space between surface and window, the fertile nexus, which was so easy to

spot in Munch's painting?

One way to approach this would be to try to describe the materiality of the surface of the image

carrier.

This is easier with Munch's painting since we can clearly name its materials. The weaving of the

canvas, the viscosity of oil paint and turpentine, the movement of Munch's hand is all right

there on the surface.

But this seems to be harder for my screen, because where exactly is the image located and what

are the materialities that shape it? The bird shit on Munch's painting fuses with the image, but

the bird shit on the screen is somehow not where the image is.

And it would by no means be sufficient to only take account of the surface of the screen.

Think about everything below it, the program structure of Photoshop in which I opened the image,

the code used for writing the operating system, all the way down to the different parts of the

hardware.

What's happening on the surface of my screen is not fixed as in the painting, but

information seems to be moving through it.

Galloway proposes to describe the interface not as a carrier or support structure of information

but an effect that takes place when 'information moves from one entity to

another'

The effect describes the forms of friction and distortion that take place when one material

passes through an interface into another material.

Munch's hand touching the canvas, the painter's hand touching the window-frame, those are

moments when 'information moves from one entity to another'. Information goes over from

the material of the flesh of Munch's hand into the material of canvas and paint. And the

friction, distortion and resistance that take place here are the effects of the painting

interface.

And this is true in the same way as the interface in front of me. The way it is built and coded,

adds an effect to the information that appears on my screen.

But in this case the effect fuses very tightly with the image on the screen. And it does so in

an almost frictionless way, as this interface is built to work, not to produce resistance

but seamlessness, more bandwidth. To facilitate a frictionless exchange between me and

everything on the other side of the screen making it easy to forget that there's a screen in

front of me and not just meaning delivered through it.

Download and Paint Like A Master

For a 2017 advertisement campaign the software developer Adobe cooperated with the Munch Museum

in Oslo that manages Munch's estate which also includes the Ekely collection.

Adobe took Munch's brushes from the Museum's archive, 3d-scanned them and created virtual

reproductions of the brushes. These were then converted into brush tools for Photoshop and could

be downloaded and used by Photoshop's users as part of the advertisement campaign.

At the end of the video clip which advertises the product a slogan flashes up on the screen:

Download and Paint Like A Master

I download Munch's Photoshop brushes, open up the reproduction of Painter by the Wall in

Photoshop and move the cursor on the screen right over Munch's brushstrokes.

My hand moves the digital stylus over the graphics tablet, only producing a silent scratching

sound while at the same time marks appear on the screen, leaving a second mark right over

Munch's.

My gestures and movement pass into the digital device and my hand applies pressure to the

touchpad. Information moves from one entity to another. The screen reacts to this and tracks and

mirrors each of my movements.

While my hand touches the graphic tablet with the stylus the marks appear somewhere entirely

else, somewhere in or behind the screen. How to describe this space, that takes up

the information of the movement of my hand?

When did I first encounter this space?

I'm thinking back about my first obsession with the computer interface when I was spending hours

and hours playing video games as a teenager.

What had sucked me into the screen back then wasn't the mouse or the keyboard or the heavy body

of the computer that I dragged to my friend's house to play World of Warcraft all night.

It wasn't the plastic and metal in front of me that the machine was made of but something in the

way that the interface in front of me worked, in the way that it did present me with a

window to a different world and that it made this in an almost seamless, immersive way.

Just like in Munch's picture, where hand and brush, body and tool fuse with one another this is

what I felt like.

A page in Galloways Interface Effect on the interface of

World of Warcraft

So if it was exactly the immersive quality of the screen that had drawn me to it, how could the

material account for this? How could it explain why the interface worked?

Every time I think about this a small detail in an oil painting by Paula Modersohn-Becker pops

up in my head.

In Still life with Apples and green glass there's this strip of wall in the back. I've

only seen the painting once a few years ago but I can very vividly remember the materiality of

this wall.

The surface of the paint had somehow fused with the depicted surface of the wall in the picture

and they seemed impossible to tell apart.

And the way the paint did hide itself perfectly behind the structure of the wall weirdly

reminded me of the way my screen hides behind everything displayed on it.

I look again at the marks that I had produced over the hand of Munch's Painter.

I see the two marks superimposed, one made in oil paint, the other in Photoshop. Now I'm

thinking that their relation to materiality might be pretty similar. They're both pretending to

be something they're not.

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Still Life with Apples and Green

Glass,1906,oil on cardboard on parquetted plywood, 33,2 x 42,9 cm

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Still Life with Apples and Green

Glass,1906,oil on cardboard on parquetted plywood, 33,2 x 42,9 cm

Hidden treasures of creativity

Adobe's ad with Munch's brushes ran under the title Hidden Treasures of Creativity,

presenting Munch's tools as holy relics. If his hand and genius are not among us anymore we can

still worship his tools, the ad suggests.

The advertisement charges the brushes with the promise of the original: Munch held this

exact brush in his hand and not any other.

That is what makes them one-of-a-kind objects, so precious that they need to be preserved in the

archive and hidden behind security doors. They bear witness to their own time and to Munch.

This is the logic of the aura, and if I wanted to embark on this logic, is there really any

other way to approach the brushes but to see them live, with my own eyes?

There would have been no use in just seeing them on my computer in just downloading them,

as 'even the most perfect reproductions, one thing is lacking: the here and now'

Here meaning: the archive of the Munch Museum in Oslo.

We arrived in Oslo in what must have been the first week of spring in Norway.

There was

still bits of snow and ice in corners that saw no direct sunlight and huge piles of snow in the

parks.

But it was warm outside and the sun glimmered on the surface of the water in the fjord.

Me standing in front of Munch's grave

Me standing in front of Munch's grave

At the museum I was greeted by one of the curators that had allowed me to see the brushes and

the Painter by the Wall.

I was led through an inconspicuous door next to the main entrance into the staff only part of

the museum. I was nervous when I arrived in a room where the brushes were presented to me. After

thinking about them for so long, what would it be like to see them?

There they were, in a box, neatly separated, lying next to each other. What did they make me

feel?

Not much to be honest, they lay there, mute and stoic. They had nothing to say to me, nothing to

reveal. They could have been anyone’s brushes, really. I wasn't really disappointed, maybe in

some way this was the reaction that I had expected?

So how did I get lured here? To experience their here and now ? Why did it not open up to me,

reveal anything? How did I end up there in the archive staring at what seemed to me like dead

material. Was I an idiot for making the whole way?

If it wasn’t in their here and now, where else was the promise that had brought me to Norway?

Center and Periphery

Maybe I had approached it the wrong way around, maybe I would not have needed to come to the

brushes but think about the way that they had come to me? After all, what had captured me was

maybe found in the not-here and not-now of the digital brush?

While I’m looking at the brushes right before me, I remember the advertisement, how the laser

scanner flickered over the bristles of the brushes. What exactly happened there in the scanning

process?

Are the copies that come out of this process still Munch’s brushes? How do they relate to

the brushes that I have right in front of me?

The ad promises us that it keeps an indexical connection between the two brushes via the

high-tech scanning procedure.

It promises to translate them carefully and truthfully. The precision of the procedure will

ensure that they can be sold as Munch’s brushes. If the resolution of the scan is high

enough, this will pass as Munch enough.

While the ad embraces the logic of the original object and the aura rhetorically, it enacts a

different one: The logic of the copy, of circulation and distribution.

Not one of the local, but one of transmission, of not being bound to a place, but being

everywhere at once. Where the aim is not to condense the brushes into one specific place but

saturate space with their presence.

Is Munch maybe found more in circulation than in the archive of the museum? More in the

periphery than in the center?

Maybe Munch is more Munch the more distributed he is. The more he appears everywhere, on

mugs, bedding, keyrings and kitchen towels.

Does he reside in the brushes, in the material of his paintings or maybe much more in the

distributed images of himself and his work that are eternalized in distribution?

Do these two logics clash? Or do they maybe, like the existence of this ad proves, fuel each

other?

The original objects in the archive back up their copies and the copies work like a link

pointing towards the brushes in the backend of the museum archive.

But what are these networks that Munch does circulate in?

I will try to describe them as interfaces, where information moves from one entity to

another.

How to describe the entity that the brushes’ information moves into when they’re

being scanned?

The light that is bounced back from the brush is channeled through the lens onto the camera's

sensor, saved as discrete information on a hard drive, processed through software and

distributed through networks of fiber-optic cables.

But this interface can not be reduced to its material components. I want to employ the interface

as a figure of thought to not only describe the material support structure, but also the

ideological one:

Besides the high tech scanning that copies the brushes there is also the form of the

advertisement, an interface of commercialization that wraps itself around the brushes.

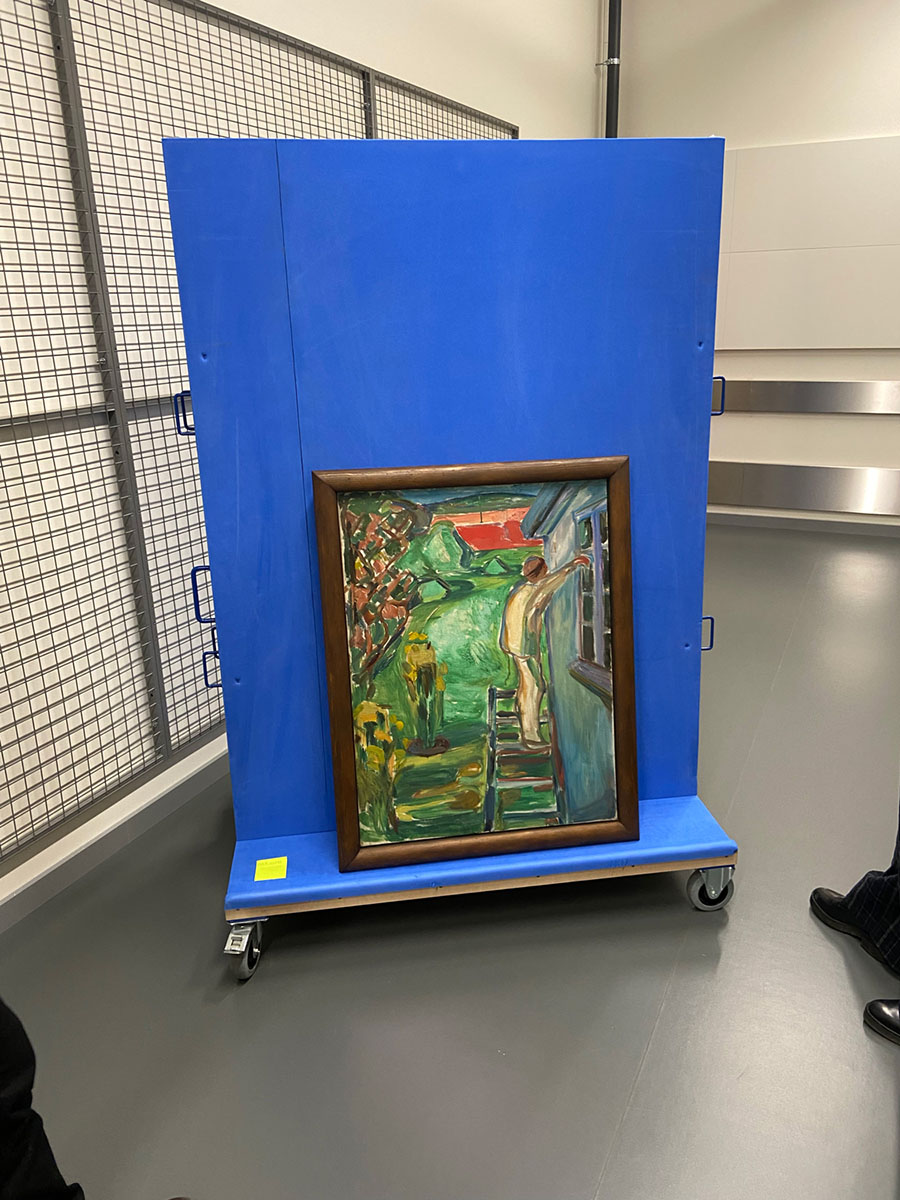

Painter by the Wall being wheeled out of the

archive

Painter by the Wall being wheeled out of the

archive

What we’ve learned from the Painter’s window about interfaces is also true here:

The more an interface conceals itself, the better it works.

For the interface of the advertisement that means: The more concealed its intentions and

mechanics are, the less it seems like an advertisement and the better it works in convincing us

of the product it’s advertising.

This part of the interface is an ideological interface, one that extracts Munch like a

ressource from the brushes and turns it into a commodity.

The brushes are subject to the specific interface effect, that repackages them to be able

to flow through this interface. When they have moved through this interface they are modified,

an effect has laid itself over them. They are converted into digital files and have become a

prop in a commercial.

What does that mean for me when I pick up these brushes and work with them?

I am just as immersed into the rules and logic of marketing and commercialisation as these

brushes are.

What does it mean for me to be inside this capitalist interface? How much of this ideological

interface is invisible, how much can be made visible?

Like the interface 'an ideological position can never be really successful until it is

naturalized' and it becomes an 'invisible barrier constraining thought and action

'

We leave the brushes and move further through the labyrinth of the museum building, where the

Painter by the Wall is waiting for me.

Standing in front of him I am thinking: Does the Painter know that he’s a worker and an

artist at the same time?

Is he content with being a house painter or does he want to be an artist?

Does he dream of his shit turning into oil paint or is he worried his paintings are all shit?